By SARAH WILDMAN

Published: February 4, 2007

E-MAIL

- SINGLE-PAGE

- REPRINTS

- SHARE

IT is past midnight in downtown Strasbourg, and hip-hop and remixed dance classics reverberate around Living Room, a red-walled lounge packed with fashionistas sipping cocktails. Around the corner, a small rave begins at Salamander, a former factory space whose new owners have skimped on every detail, letting the dance floor speak for itself. Across town, a 30-something crowd chatters amicably at Les Aviateurs, a Chicago-style rock bar with décor that blends old movie and concert posters with early-20th-century model airplanes.

Go to the Strasbourg Travel Guide »

Multimedia

The Midnight Train to Strasbourg

Have you been to Strasbourg?

Share Your Suggestions

Where to Stay | Where to Eat |What to Do

The New York Times

Night life has never been a selling point in Strasbourg, but then this is a city in transition.

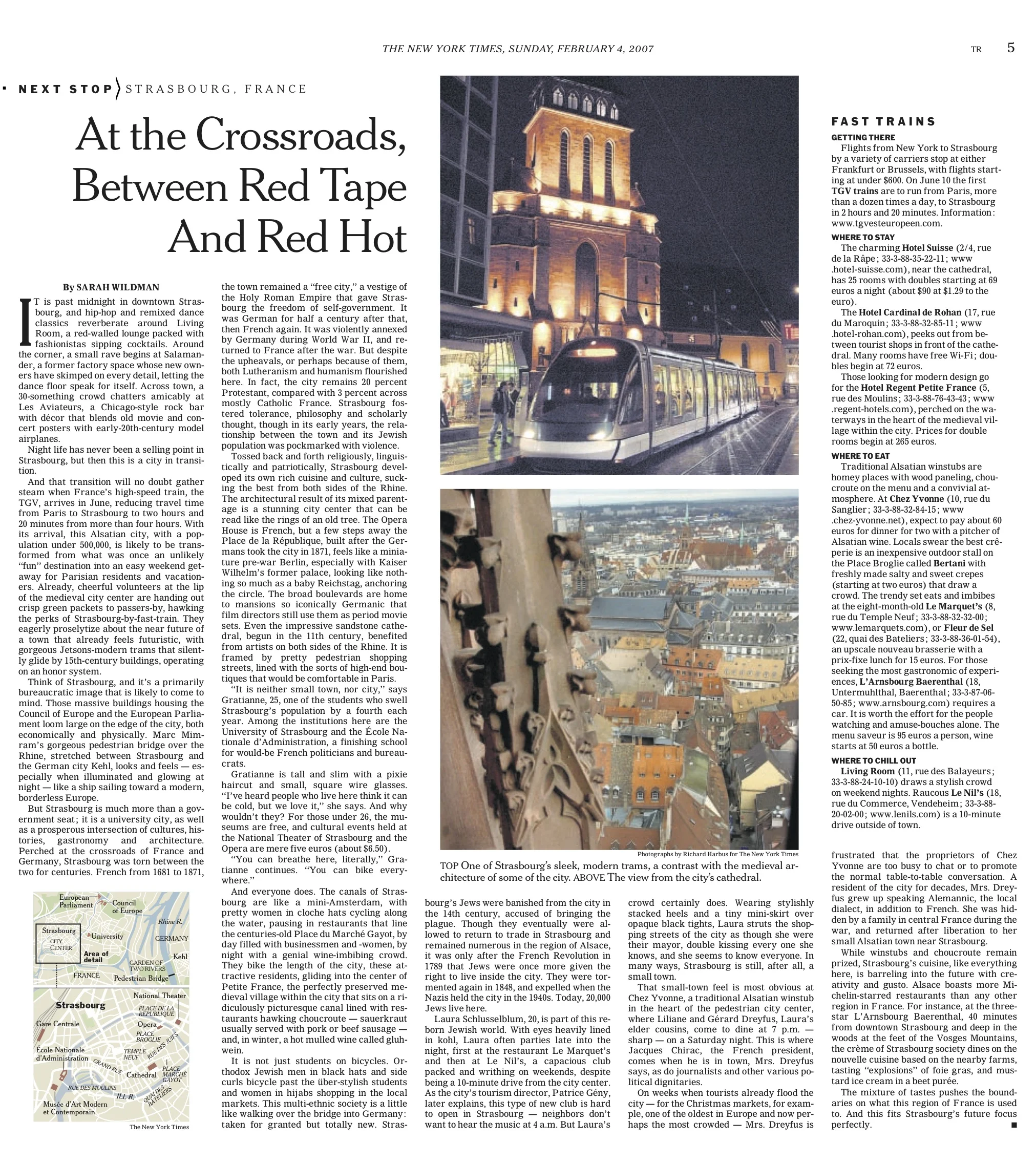

And that transition will no doubt gather steam whenFrance's high-speed train, the TGV, arrives in June, reducing travel time from Paris to Strasbourg to two hours and 20 minutes from more than four hours. With its arrival, this Alsatian city, with a population under 500,000, is likely to be transformed from what was once an unlikely “fun” destination into an easy weekend getaway for Parisian residents and vacationers. Already, cheerful volunteers at the lip of the medieval city center are handing out crisp green packets to passers-by, hawking the perks of Strasbourg-by-fast-train. They eagerly proselytize about the near future of a town that already feels futuristic, with gorgeous Jetsons-modern trams that silently glide by 15th-century buildings, operating on an honor system.

Think of Strasbourg, and it's a primarily bureaucratic image that is likely to come to mind. Those massive buildings housing the Council of Europe and the European Parliament loom large on the edge of the city, both economically and physically. Marc Mimram's gorgeous pedestrian bridge over the Rhine, stretched between Strasbourg and the German city Kehl, looks and feels — especially when illuminated and glowing at night — like a ship sailing toward a modern, borderless Europe.

But Strasbourg is much more than a government seat; it is a university city, as well as a prosperous intersection of cultures, histories, gastronomy and architecture. Perched at the crossroads of France and Germany, Strasbourg was torn between the two for centuries. French from 1681 to 1871, the town remained a “free city,” a vestige of the Holy Roman Empire that gave Strasbourg the freedom of self-government. It was German for half a century after that, then French again. It was violently annexed by Germany during World War II, and returned to France after the war. But despite the upheavals, or perhaps because of them, both Lutheranism and humanism flourished here. In fact, the city remains 20 percent Protestant, compared with 3 percent across mostly Catholic France. Strasbourg fostered tolerance, philosophy and scholarly thought, though in its early years, the relationship between the town and its Jewish population was pockmarked with violence.

Tossed back and forth religiously, linguistically and patriotically, Strasbourg developed its own rich cuisine and culture, sucking the best from both sides of the Rhine. The architectural result of its mixed parentage is a stunning city center that can be read like the rings of an old tree. The Opera House is French, but a few steps away the Place de la République, built after the Germans took the city in 1871, feels like a miniature pre-warBerlin, especially with Kaiser Wilhelm's former palace, looking like nothing so much as a baby Reichstag, anchoring the circle. The broad boulevards are home to mansions so iconically Germanic that film directors still use them as period movie sets. Even the impressive sandstone cathedral, begun in the 11th century, benefited from artists on both sides of the Rhine. It is framed by pretty pedestrian shopping streets, lined with the sorts of high-end boutiques that would be comfortable in Paris.

“It is neither small town, nor city,” says Gratianne, 25, one of the students who swell Strasbourg's population by a fourth each year. Among the institutions here are the University of Strasbourg and the École Nationale d'Administration, a finishing school for would-be French politicians and bureaucrats.

Gratianne is tall and slim with a pixie haircut and small, square wire glasses. “I've heard people who live here think it can be cold, but we love it,” she says. And why wouldn't they? For those under 26, the museums are free, and cultural events held at the National Theater of Strasbourg and the Opera are a mere five euros (about $6.50).

“You can breathe here, literally,” Gratianne continues. “You can bike everywhere.”

And everyone does. The canals of Strasbourg are like a mini-Amsterdam, with pretty women in cloche hats cycling along the water, pausing in restaurants that line the centuries-old Place du Marché Gayot, by day filled with businessmen and -women, by night with a genial wine-imbibing crowd. They bike the length of the city, these attractive residents, gliding into the center of Petite France, the perfectly preserved medieval village within the city that sits on a ridiculously picturesque canal lined with restaurants hawking choucroute — sauerkraut usually served with pork or beef sausage — and, in winter, a hot mulled wine called glühwein.

It is not just students on bicycles. Orthodox Jewish men in black hats and side curls bicycle past the über-stylish students and women in hijabs shopping in the local markets. This multi-ethnic society is a little like walking over the bridge into Germany: taken for granted but totally new. Strasbourg's Jews were banished from the city in the 14th century, accused of bringing the plague. Though they eventually were allowed to return to trade in Strasbourg and remained numerous in the region of Alsace, it was only after the French Revolution in 1789 that Jews were once more given the right to live inside the city. They were tormented again in 1848, and expelled when the Nazis held the city in the 1940s. Today, 20,000 Jews live here.

Laura Schlusselblum, 20, is part of this reborn Jewish world. With eyes heavily lined in kohl, Laura often parties late into the night, first at the restaurant Le Marquet's and then at Le Nil's, a capacious club packed and writhing on weekends, despite being a 10-minute drive from the city center. As the city's tourism director, Patrice Gény, later explains, this type of new club is hard to open in Strasbourg — neighbors don't want to hear the music at 4 a.m. But Laura's crowd certainly does. Wearing stylishly stacked heels and a tiny mini-skirt over opaque black tights, Laura struts the shopping streets of the city as though she were their mayor, double kissing every one she knows, and she seems to know everyone. In many ways, Strasbourg is still, after all, a small town.

That small-town feel is most obvious at Chez Yvonne, a traditional Alsatian winstub in the heart of the pedestrian city center, where Liliane and Gérard Dreyfus, Laura's elder cousins, come to dine at 7 p.m. — sharp — on a Saturday night. This is where Jacques Chirac, the French president, comes when he is in town, locals say, as do journalists and other various political dignitaries.

On weeks when tourists already flood the city — for the Christmas markets, for example, one of the oldest in Europe and now perhaps the most crowded — Mrs. Dreyfus is frustrated that the proprietors of Chez Yvonne are too busy to chat or to promote the normal table-to-table conversation. A resident of the city for decades, Mrs. Dreyfus grew up speaking Alemannic, the local dialect, in addition to French. She was hidden by a family in central France during the war, and returned after liberation to her small Alsatian town near Strasbourg.

While winstubs and choucroute remain prized, Strasbourg's cuisine, like everything here, is barreling into the future with creativity and gusto. Alsace boasts more Michelin-starred restaurants than any other region in France. For instance, at the three-star L'Arnsbourg Baerenthal, 40 minutes from downtown Strasbourg and deep in the woods at the feet of the Vosges Mountains, the crème of Strasbourg society dines on the nouvelle cuisine based on the nearby farms, tasting “explosions” of foie gras, and mustard ice cream in a beet purée.

The mixture of tastes pushes the boundaries on what this region of France is used to. And this fits Strasbourg's future focus perfectly.

VISITOR INFORMATION

GETTING THERE

Flights from New York to Strasbourg by a variety of carriers stop at either Frankfurt orBrussels, with flights starting at under $600. On June 10 the first TGV trains are to run from Paris, more than a dozen times a day, to Strasbourg in 2 hours and 20 minutes. Information: www.tgvesteuropeen.com.

WHERE TO STAY

The charming Hotel Suisse (2/4, rue de la Râpe; 33-3-88-35-22-11; www.hotel-suisse.com), near the cathedral, has 25 rooms with doubles starting at 69 euros a night (about $90 at $1.29 to the euro).

The Hotel Cardinal de Rohan (17, rue du Maroquin; 33-3-88-32-85-11; www.hotel-rohan.com), peeks out from between tourist shops in front of the cathedral. Many rooms have free Wi-Fi; doubles begin at 72 euros.

Those looking for modern design go for the Hotel Regent Petite France (5, rue des Moulins; 33-3-88-76-43-43; www.regent-hotels.com), perched on the waterways in the heart of the medieval village within the city. Prices for double rooms begin at 265 euros.

WHERE TO EAT

Traditional Alsatian winstubs are homey places with wood paneling, choucroute on the menu and a convivial atmosphere. At Chez Yvonne (10, rue du Sanglier; 33-3-88-32-84-15; www.chez-yvonne.net), expect to pay about 60 euros for dinner for two with a pitcher of Alsatian wine. Locals swear the best crêperie is an inexpensive outdoor stall on the Place Broglie called Bertani with freshly made salty and sweet crepes (starting at two euros) that draw a crowd. The trendy set eats and imbibes at the eight-month-old Le Marquet's (8, rue du Temple Neuf; 33-3-88-32-32-00; www.lemarquets.com), or Fleur de Sel (22, quai des Bateliers; 33-3-88-36-01-54), an upscale nouveau brasserie with a prix-fixe lunch for 15 euros. For those seeking the most gastronomic of experiences, L'Arnsbourg Baerenthal(18, Untermuhlthal, Baerenthal; 33-3-87-06-50-85; www.arnsbourg.com) requires a car. It is worth the effort for the people watching and amuse-bouches alone. The menu saveur is 95 euros a person, wine starts at 50 euros a bottle.

WHERE TO CHILL OUT

Living Room (11, rue des Balayeurs; 33-3-88-24-10-10) draws a stylish crowd on weekend nights. Raucous Le Nil's (18, rue du Commerce, Vendeheim; 33-3-88-20-02-00;www.lenils.com) is a 10-minute drive outside of town.