Our Lost Warsaw Ghetto Diary

My relative wrote one of the Shoah’s most revealing documents. Why doesn’t anyone know of it?

“Jews began to write,” wrote Emmanuel Ringelblum, the most famous Warsaw Ghetto chronicler, recalling efforts to document the destruction. Ringelblum founded the Oneg Shabbat group, the collection of “journalists, writers, teachers, public figures, youth, even children,” who decided they would record their experiences. The group buried an archive of selected materials, to bear witness. “A great deal was written,” Ringelblum recounted, before his own murder, “but most of it was lost during the deportations and extermination of Warsaw’s Jews. Only the material hidden in the ghetto archive remained.”

That’s what Ringelblum believed.

But missing from the famous ghetto archive is the diary of a man named Reuven Ben-Shem. About 800 pages long, penned in minuscule handwriting that is almost impossible to read with the naked eye, the diary is a remarkable account, clear-eyed and poignant, spanning roughly the time from the establishment of the ghetto to the arrival of Soviet troops in Warsaw. It contains references to everything its author had ever studied—from Mishnah and Torah to secular literature and the work of Sigmund Freud, with whom Ben-Shem learned in Vienna in the interwar period—as well as a close observation of the ways in which Jews were forced to become animals, not metaphorically, but actually. And it is written in modern Hebrew. “It is a fabulous document,” said Amos Goldberg, senior lecturer in Holocaust Studies at the Department of Jewish History at the Hebrew University in Jerusalem, who recently wrote a book on Holocaust diaries. “It has incredible descriptive force.”

February 1942. The street is teeming with sights so maddening, so depraved that it is hard to find any equivalent in the treasury of humanity’s degradation. There is no doubt that the denizens of the jungle and animals will never behave this way. The dead are naked. When someone had just starved, they cover him in wrapping paper and lie him down on the sidewalk, and at night his friends, or just beggars, walk out, and undress him completely, and leave him all naked with no shoes, no dress or even underwear. And in the morning, as you go out in the street and the wind blows off the wrapping papers covering the dead, you see the organs of men, women and children all scrawny, the quivering organs of death in the street. You see the naked bodies, frozen stuck to the sidewalk. The body becomes one with the stone, congealed. One dead chunk screaming with poverty and disgust.

Ben-Shem kept his diary in a leather satchel that he carried with him from the ghetto to the Aryan side of Warsaw, to Lublin, through Romania and onto the illegal ship that ferried him to Palestine in 1946. It remained in the family home until about four years ago when his Israeli-born son Kami showed all 800 pages, stored exactly as it had been in Warsaw, to a researcher named Laurence Weinbaum, who had stumbled upon the name Reuven Ben-Shem dotted throughout Chaim Lazar’sMuranowska 7, a biography of the Revisionist Zionist underground in the Warsaw Ghetto. Intrigued, Weinbaum tracked down the Ben-Shem family and was eventually invited to see what the family had at home. “You can imagine it felt like the moment when the Bedouin presented the Dead Sea scrolls,” he told me, during a recent interview in his Jerusalem office.

What Weinbaum found was, in his opinion, one of the most important works of first-person narrative to have survived the Shoah. The diary, he says, “is extraordinary for several reasons: one it is contemporaneous. It is also in Hebrew. Most of the diarists wrote in Yiddish or Polish. And Feldschuh (Ben-Shem’s original name) had extraordinary intellectual horizons.” He was also, points out Havi Dreyfus, a senior lecturer in the department of Jewish History at the University of Tel Aviv, a broad observer, from the deportations, to religious life, to the extremes of ghetto poverty—to intense, painful, descriptions of his desperate desire to allow his young daughter Josima, a piano prodigy, to live. He was a brilliant Hebraist and fluent in—at least—three other languages. Agrees David Silberklang, senior historian at Yad Vashem, “What Reuven Feldschuh did was of great significance. It will be a huge book if the entire diary is published.” Silberklang believes that the diary is “potentially similar to” the impact Victor Klemperer’s diaries had in the 1990s, “because of the quality of the writer and the richness of experience and expanse of years.”

I wouldn’t know of Reuven Ben-Shem’s diary, either, except that he was my grandfather’s first cousin.

***

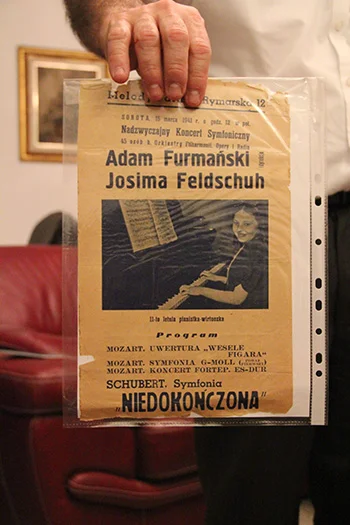

Late on a recent Friday night in the Tel Aviv suburb of Ramat Gan, I attended a Shabbat dinner. At some point, the guests moved from table to couch, and an array of liquors was lined up on the coffee table. Our host, Kami Ben-Shem, receded into a back room and returned with a selection of crumbling, yellow paper. The first page—kept in a plastic sleeve, the sort that might be used by children in a binder for school—was an announcement for a concert.

Poster for Josima’s concert (Sarah Wildman)

“15 March 1941” it is dated, at the top, “Josima Feldschuh” it says, above the image of a rosy-cheeked girl with a bow in her hair, sitting at a piano, and then, below her photo, it is written in Polish, “11 year old piano virtuoso.” The program promises selections from Mozart’s Marriage of Figaro and Schubert’s Unfinished Symphony, a concert held at Rymarska 12, the heart of the Warsaw Ghetto. Two years later, the girl, Kami’s half-sister, was smuggled to the Aryan side just before the uprising. Her father had feared her death for all his months in the ghetto.

January 1942. There’s talk recently of the vandals murdering the children and the blood of all the fathers hardens in their veins as they listen to such whispers… I returned home and I am all shaken. My child is sleeping, I am looking at her. My eye deceives me and I don’t see her. She disappears, the bed grows empty. I was frightened. I bent over and held her so forcefully that she woke up, quizzical and afraid. She calmed down as she saw me, and her face radiated with a lovely smile. She sent me a kiss by air, turned over to her side, and fell asleep. Inside of me fritters a demon of fear.

Josima died of tuberculosis some weeks after she went into hiding; soon after, her mother, Pnina, a musicologist, took her own life. Only Reuven survived. After the war, Reuven never spoke of Josima, but her framed photo hung like a ghostly mezuzah in the doorway to his home, so each member of Ben-Shem’s new postwar family would see her as they came in and as they went out.